All Eyes

Art Paris, Grand Palais

Paris, 2025

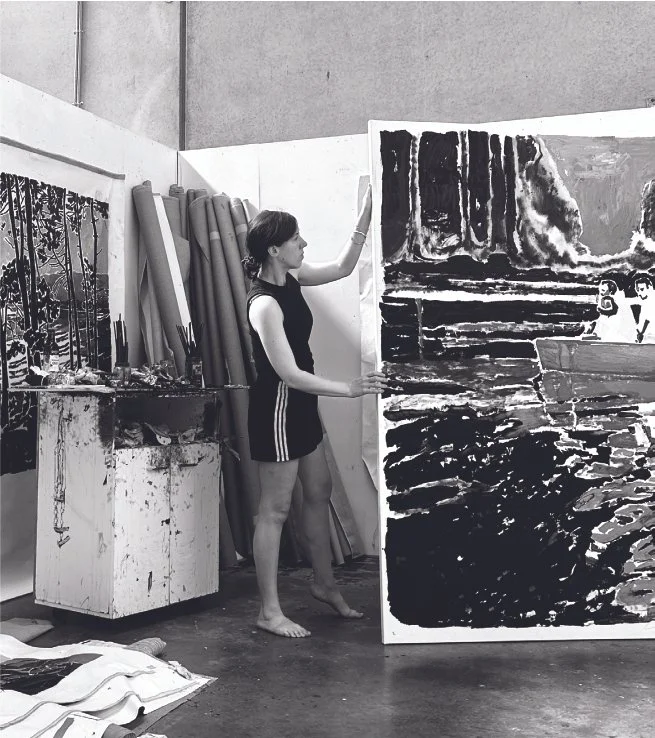

Clara Adolphs almost always paints from found photographs. A key part of her practice, she is not only a painter but an obsessive collector of images and memories. In her collecting she has gathered a ghostly archive of what the 20th century looked like. Each photograph offers a glimpse into a past life, place, and circumstance. Frequently, Adolphs lacks context regarding her source images, which often come from deceased estates, photo albums sold on eBay, flea markets, or antique stores. Many are personal snapshots lost long ago or left behind by their original creators.

Despite the considerable differences in societal, cultural, and political conditions between her and her subjects, she seeks commonalities and shared experiences, striving for recognition in the unknowable nature of those captured in the photographs. These are authentic documents and resonant objects, and the artist addresses them from her own subjective, emotional state. Within the artist’s studio, through processes of filtering and selection, the images undergo a process of rebirth. Adolphs work exemplifies her ability to bridge the personal and something more universal. She thinks of her vast archive as an experiment in collective memory, which is shared with her viewers.

"All Eyes" (1), 2025, oil on linen, 200 x 318 cm

"All Eyes" (2), 2025, oil on linen, 200 x 315 cm

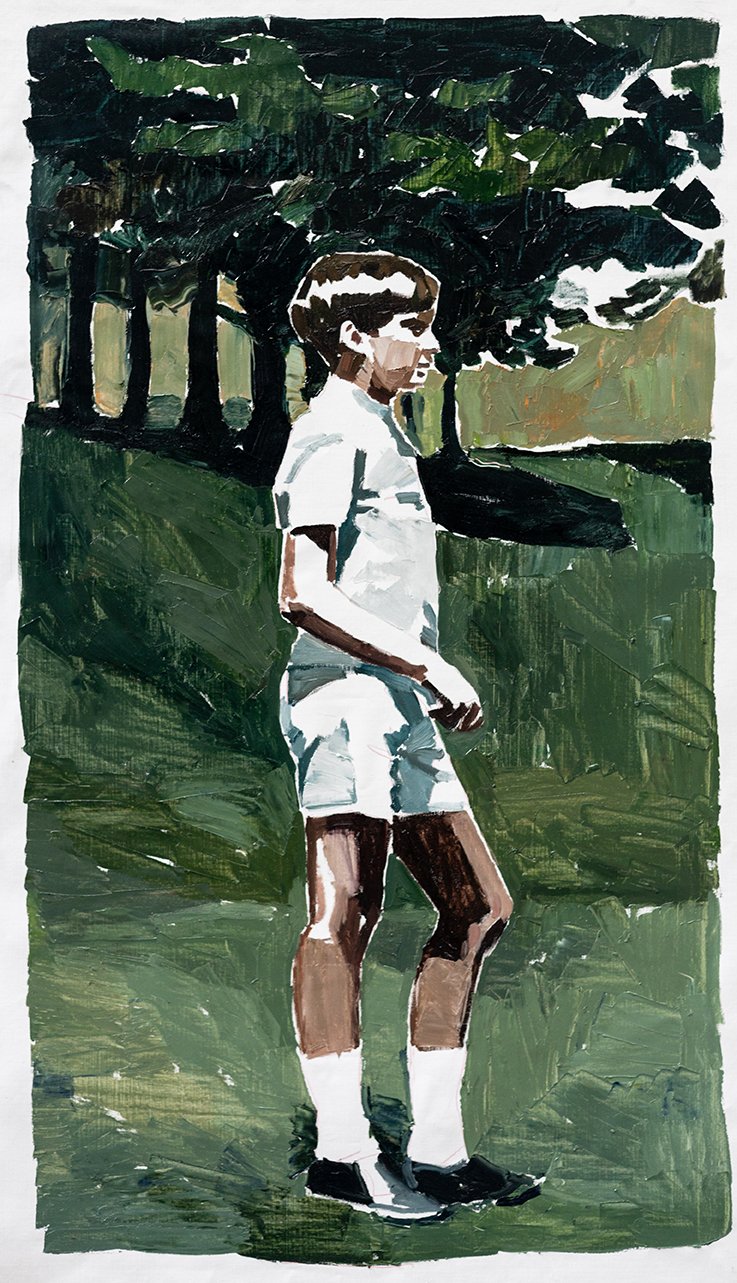

"Boy, Green Field", 2025, oil on linen, 130 x 75 cm

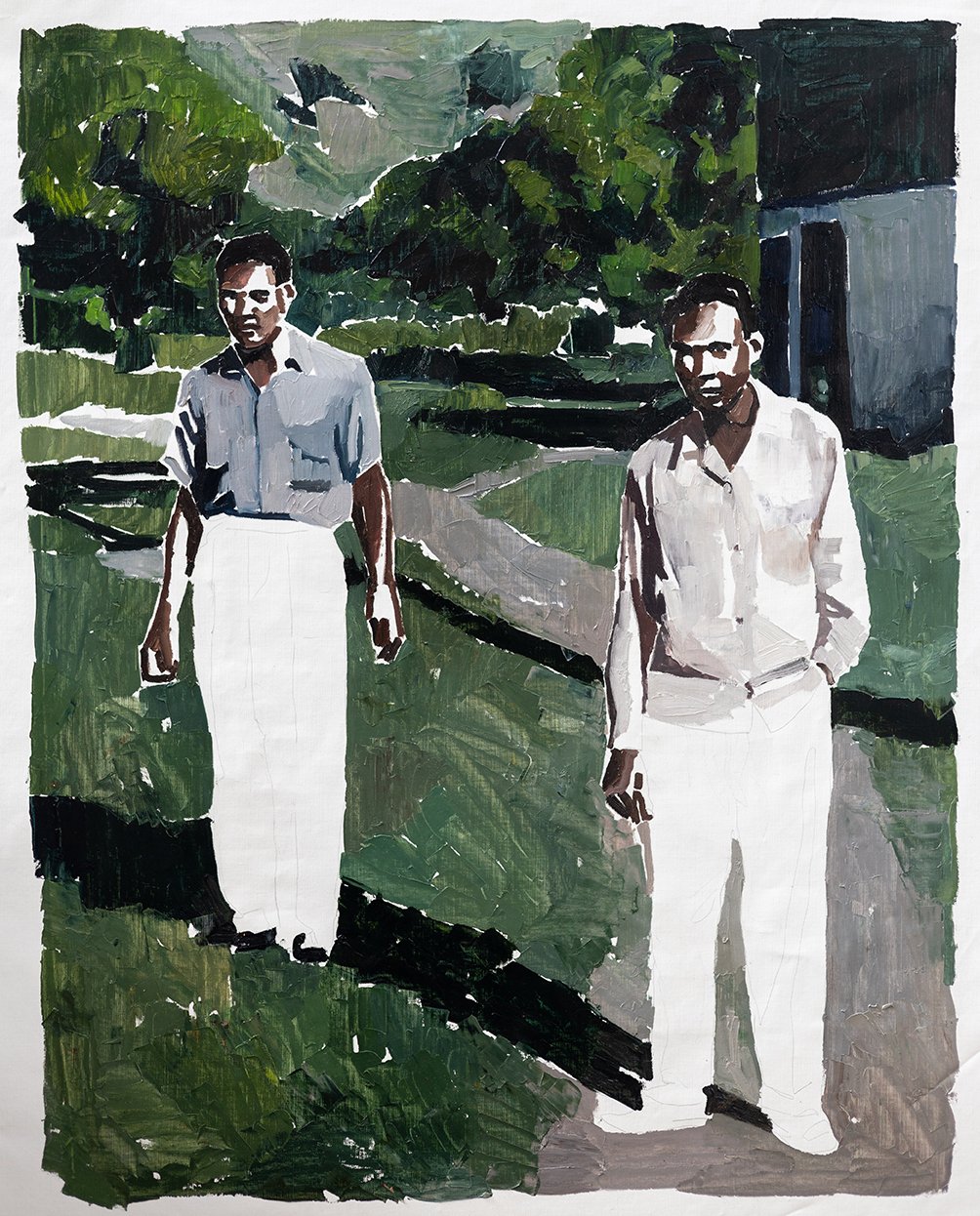

"Boys", 2025, oil on linen, 166 x 256 cm

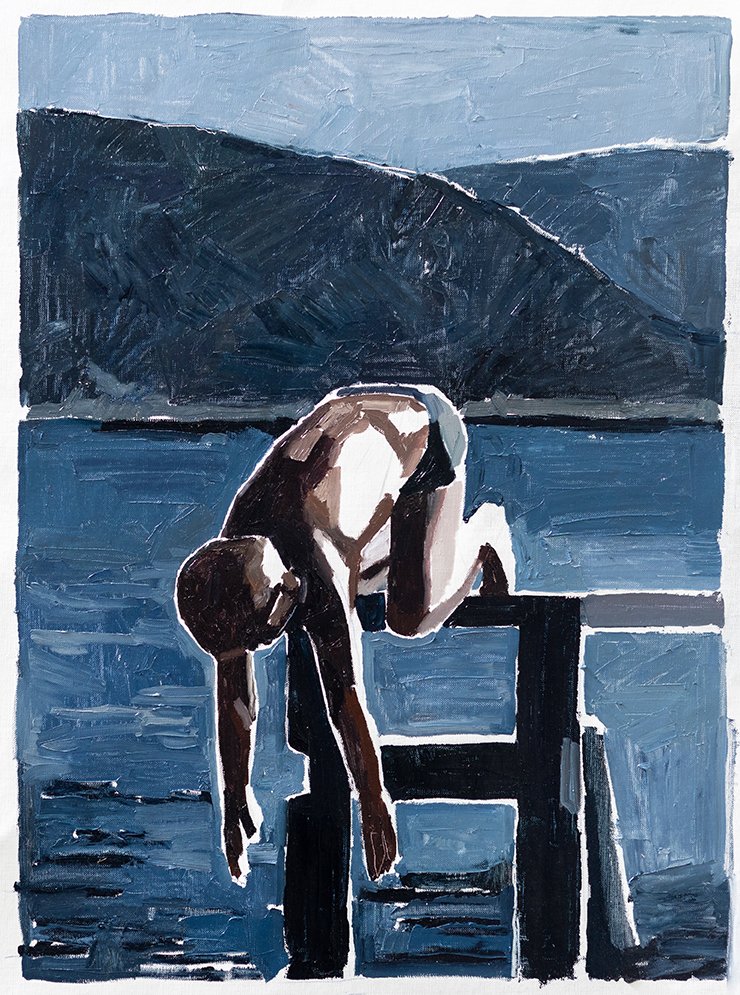

"Dive", 2025, oil on linen, 91.5 x 68 cm

"Group, Sundown", 2025, oil on linen, 163 x 226 cm

"Her Side I", 2025, oil on linen, 87 x 70 cm

"Her Side II", 2025, oil on linen, 89 x 71.5 cm

"High Water II (Detail)", 2025, oil on linen, 94 x 74 cm

"High Water (Postcard)", 2025, oil on linen, 162 x 225 cm

Although the audience is not privy to the source material, post-war European imagery often dominates. Adolphs is exploring and re-picturing the period in which photography was becoming truly accessible and widespread for the first time. From the 1950s onward in particular, Europeans were becoming amateur photographers, documenting civil and domestic life. This was happening concurrently to mass migration and rebuilding, a return to normalcy which was also the beginning of something entirely new. This period, known as the ‘great acceleration’, in human population, industrialisation, carbon emissions, was, among many other things, also a great acceleration in our ability to document and capture, to reproduce the world infinitely, with gusto and fidelity.

This process of capture is a powerful relational force, one may lay claim to an unreal past, fill in gaps and rewrite history, it can also provide a sense of security in unfamiliar spaces. In the post-war context, the evolution of photography paralleled the rise of modern tourism, as large numbers of people began to travel outside their habitual environments and pose before or simply document foreign landscapes. Photographic images like these provide most of the knowledge we have about the look of the past.

Adolphs’ passion for collecting was ignited by the extensive family albums cherished by her parents, which contained images of relatives. From a young age Clara found herself transfixed by the Germans and Latvians who populate the albums, individuals she had not met but about whom she harboured a profound curiosity. This is a common experience in the children of migrants, as they often maintain a meaningful connection to a culture despite geographic and even temporal distance.

As Susan Sontag highlighted, the majority of people who make photographs do not do so as artists. Instead, they document in an effort to preserve memories, to stem the flow of time, as form of personal insurance against what has passed. These are not art forms, but traces of history. Adolphs’ work and intention, as a contemporary observer and collector, is to transforms these ordinary moments into art. That is the sorcery of the artist, breathing new life into faded prints, families or hiking groups who stood on the sides of mountains and lakes. Adolphs often focuses on subjects who engage with the camera, staring down the lens, they manage to look back, an effect of intensity and depth. By creating paintings, she elevates her subjects into a new context, shifting their representation from private into a public arena.

"His Back I", 2025, oil on linen, 68 x 56 cm

"His Back II", 2025, oil on linen, 52.5 x 69 cm

"Men In The Woods", 2025, oil on linen, 192 x 171 cm

"Mountain View", 2025, oil on linen, 156.5 x 137 cm

"Nightshade (Detail)", 2025, oil on canvas, 155.5 x 150 cm

"Nightshade (Postcard)", 2025, oil on linen, 163 x 231 cm

"School Boy I", 2024, oil on linen, 52 x 52.5 cm

"School Boy III", 2024, oil on linen, 52 x 52.5 cm

"School Boy IV", 2024, oil on linen, 52 x 49.5 cm

"Shallow Tide", 2025, oil on linen, 144 x 245 cm

"Sky Over Mountain Pass II", 2025, oil on linen, 165 x 232.5 cm

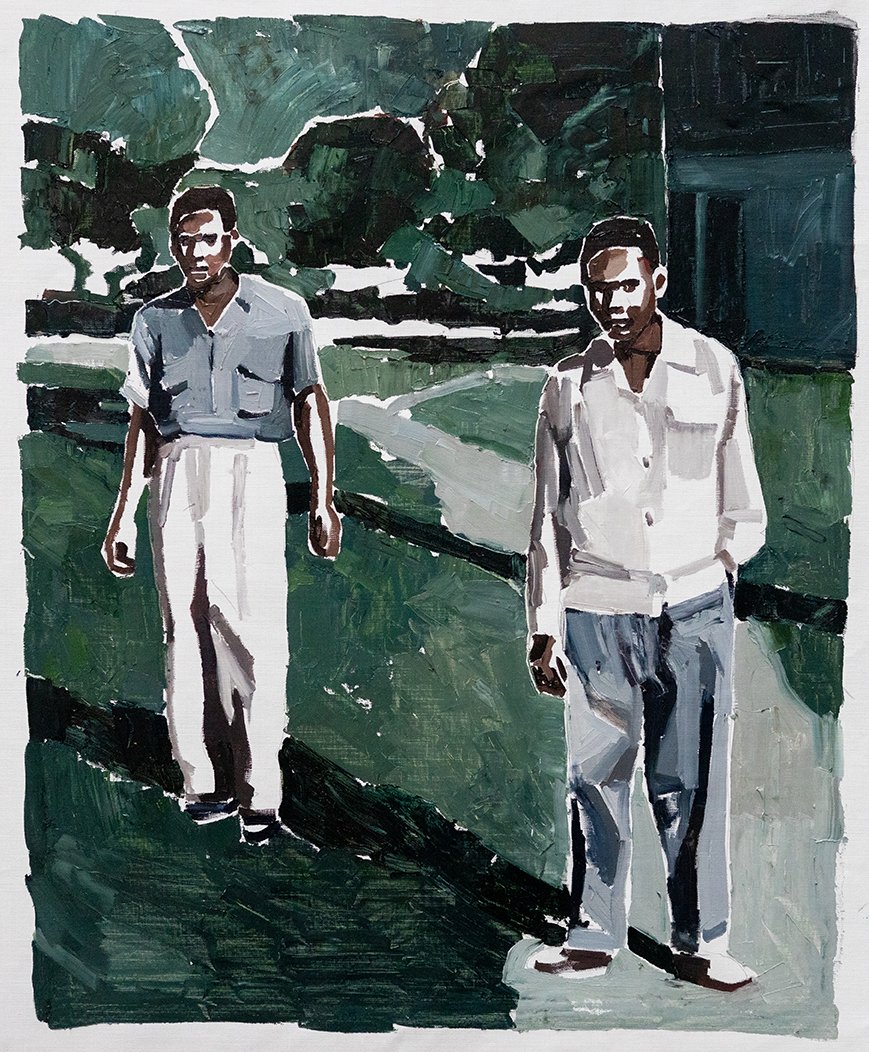

"Two Men I", 2025, oil on linen, 124 x 99 cm

"Two Men II", 2025, oil on linen, 91.5 x 76.5 cm

"Women and Reflection", 2025, oil on linen, 169 x 269 cm

While photography is often viewed as an act of non-intervention, something invasive which nevertheless maintains a distance, and is prone to generating unequal power dynamics, Adolphs’ creative process involves manipulation and intimacy. She is drawn in by the photographs’ lack of visual clarity, which, can be fleshed out like a memory.

Much like a photographer burning through a roll of film, or space on the aptly named ‘memory’ card, Adolphs experiments with repetition and recapture. Here these iterative series emulate a negative or contact sheet, where the photographer has committed several exposures to the one composition. The painting dramatically slows down this process, dragging it out over multiple days and across numerous canvases. She is deeply invested in the scene, and exploring the thrill of finding one perfectly composed image on a contact sheet. These repeated images are marked by subtle variations, such repetition is now a defining feature of Adolphs’ artistic approach, as evident in the studio as it is in the gallery.

These differences within the series imitate the technical realities faced by the photographer. The photographer trades between various settings, aperture, shutter speed and film speed, each is adjusted in relation to the others, with consequences for focal length, clarity and exposure. The way Clara paints replicates this process, there is always an exchange of elements, a cross hatch between paint and exposed, white canvas. It might depict a blown out rockface or branch, an ‘over exposed’ forehead or cheek, or sunlight on the water’s surface. But these ‘blank spots’ are always an illusion of an absence, in a good exchange nothing is left behind, and in this manner the canvas is always a source of information. Her technique integrates wet and dry brush marks alongside the use of palette knives, leading to distinct variations between each iteration. Clara’s use of gestural mark-making captures the ephemeral nature of a moment, constantly adding and subtracting from her canvas. This dynamic interplay of elements causes one component to yield to another.

A signature that has developed over the past decade, Adolphs’ final works are considerably larger in scale when compared to their source material. This enlargement process compels her to imaginatively recreate the details that may be lost, resulting in canvases that radiate motion and energy. The artist’s intent extends beyond mere replication, she aims to revive the original image through movement, texture, colour, and scale.

In 2024, Adolphs participated in the Adelaide Biennial, titled Inner Sanctum, curated by José Da Silva. For this exhibition, she presented a series of paintings produced from candid photographs featuring groups within landscapes, solitary figures, and cloud formations. The Biennial encompassed a variety of exhibitions, performances, and discussions, all aimed at exploring the ways in which we engage with both the world and one another. The concept of an inner sanctum represents the private or sacred spaces we cultivate, as well as our imaginative capacity to perceive culture and society from new perspectives.

Following the Adelaide Biennial, a significant survey exhibition titled Together Again was held at Ngununggula, Southern Highlands Regional Gallery, in New South Wales. This exhibition showcased an extensive collection of artworks created over the past decade, paired with new commissions. It not only illustrated the evolution and development of her artistic practice but sought to rearticulate her oeuvre to that point. The title Together Again evokes a sense of reunion, reminiscent of gathering with long-lost friends, while acknowledging the convergence of past works that reflect pivotal moments in the artist’s journey.

– Milena Stojanovska, 2025